Calumniada por ojos y murmullos, sospechosa tanto para algunos colegas varones como para los árbitros de las "buenas costumbres", Eduarda Mansilla de García (Buenos Aires, 1834-1892) se empeña apasionadamente en una tarea que las normas de su tiempo juzgan antinatural para la condición femenina: acceder a los frutos prohibidos de la creación.

Está dispuesta a pagar, incluso, el precio de poner un océano de por medio entre esta vocación y su núcleo familiar (marido y seis hijos), a los que dejará en Europa durante varios años para volver a la Argentina y dar a conocer su obra.

Sobrina preferida de Juan Manuel de Rosas, hija de Agustina y hermana de Lucio Victorio, esposa de Manuel Rafael García, Eduarda quiere existir por mérito propio. Aspira a trascender tanto los parentescos prestigiosos como los roles permitidos al "segundo sexo": ícono de belleza y de maternidad, decide ser una artista y no un mero adorno ocasional de los salones.

Una mujer de fin de siglo narra así, en tres etapas, una aventura vital y los deseos de quien no está dispuesta a aceptar resignadamente los mandatos sociales.

Este intenso texto de María Rosa Lojo, autora de la exitosa novela La princesa federal, diseña desde el trabajo del lenguaje y el debate del pensamiento un personaje inolvidable que, como su contemporánea Nora Helmer, la heroína de Ibsen, también se verá enfrentada a una decisión extrema: abandonar su "casa de muñecas" para poder cumplir con el primero de los deberes: el que todo ser humano tiene para consigo mismo.

MARÍA ROSA LOJO nació en Buenos Aires en 1954. Ha publicado Visiones (1984, Primer Premio de Poesía de la Feria del Libro y Tercer Premio Municipal), Marginales (1986, cuentos) y Canción perdida en Buenos Aires al Oeste (1987, novela), ambos premiados por el Fondo Nacional de las Artes; Forma oculta del mundo (1991, Primer Premio de Poesía Dr. Alfredo Roggiano, Tercer Premio Regional a la Producción Literaria y Segundo Premio Municipal), La pasión de los nómades (1994, novela finalista del Premio Planeta, Primer Premio Municipal "Eduardo Mallea" y única mención especial del Premio Nacional de Narrativa) y La princesa federal (novela, 1998). En 1991 le fue concedida la beca de la Fundación Antorchas destinada a "artistas sobresalientes en los comienzos de su plenitud creativa". Como ensayista publicó, en 1994, La "barbarie" en la narrativa argentina (siglo XIX), y en 1997, Sabato: en busca del original perdido, Cuentistas

argentinos de fin de siglo, Estudio Preliminar y El símbolo: poéticas, teorías, metatextos (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), además de numerosos trabajos en revistas universitarias y especializadas.

Es doctora en Filosofía y Letras por la Universidad de Buenos Aires y se desempeña como investigadora del CONICET. Ha sido conferencista y profesora visitante en diversas universidades de la Argentina y del extranjero, y ha participado como escritora invitada en ferias del libro y congresos internacionales. Es colaboradora permanente de las revistas CULTURA y FIRST, y del Suplemento de Cultura de LA NACIÓN.

http://www.4shared.com/file/fQjxzJyW/Lojo_Mara_Rosa_-_Una_Mujer_de_.html

[Se han eliminado los trozos de este mensaje que no contenían texto]

domingo, 31 de octubre de 2010

Una mujer de fin de siglo - Ma. Rosa Lojo

Mastretta y Sor Juana

Angeles Mastretta

Ángeles Mastretta es escritora. Quizás ninguna otra vocación le guste más. Sin embargo, también puede ser escucha incondicional, cantante insoportable, conversadora irredenta. Hace su trabajo sin la debida asiduidad, pero cuando quiere consigue abismarse en lo que ama. Nació y vive en México.

Sus libros son "Arráncame la vida", "Mujeres de ojos grandes"," Mal de amores", "Puerto Libre", "El mundo iluminado", "El cielo de los leones", "Ninguna eternidad como la mía" y "Maridos". Están publicados en todo el mundo de habla hispana y viajan con asiduidad por los idiomas varios de otros mundos. Han sido traducidos a veinte idiomas.

PALABRAS EN VOZ BAJA:

"Sólo la mano del deseo, sólo su aire fresco y estremecido, recorriéndonos, levantándonos a vivir"

Jaime Sabines

"A veces en medio de la noche, los recuerdos como luces de bengala, vuelven trascendental y policroma nuestra perplejidad."

Renato Leduc.

"Mi corazón lo diga

que en padrones eternos

inextinguibles guarda

testimonios del fuego"

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Mastretta

29 Oct 2010

Flores de cempasúchil

Escrito por: Ángeles Mastretta el 29 Oct 2010 - URL Permanente

Aparecen de pronto aunque no sea noviembre, aunque no tengamos sino lo mismo para su ofrenda, aunque sepan que maldecimos su nombre por haberse marchado, aunque estén hartos de venir siempre que les lloramos, aunque ya nada nos deban.

Así es con los amores y los muertos. Los míos, como tantos, regresan.

Siempre, aún cuando no los llamo, vuelven. A veces me amonestan, otras me escuchan, las más simplemente se ponen a mirarme.

Intervienen mis sueños, aparecen dentro de mis secretos, los conocen. Se burlan de mis miedos, me asustan recordando lo que creía olvidado.

Los míos son menos drásticos que los muertos de Juan Rulfo. Y menos enigmáticos. Esto no quiere decir que puedo manejarlos a mi antojo, pero sí que además de venir cuando ellos quieren, suelen venir cuando los llamo y entender el presente y hasta explicármelo.

Supongo que algo así le pasa a todo el mundo, que aquellos que han perdido a quienes fueron tan suyos como su índole misma, los evocan a diario con tal fuerza que los hacen volver a sentarse en la orilla de su cama, a seguirlos con la vista desde una fotografía, a pasarles la mano por la cabeza cuando creen que la vida es tan corta que no merece el cansancio.

Punto: El uno y dos de noviembre, los mexicanos recordamos con altares y flores, como comida y conversación, a nuestros bien amados muertos. Hay quienes, muchos, dejan comida sobre las tumbas, las llenan de flores, de copal, de pan, de velas.

Punto y aparte: Yo había podido hacer eso muchas veces, les enseñé a mis hijos a poner altares y todos los noviembres se llenaba mi casa de cempasúchil. Este año no podré. No he querido. A mis muertos de siempre los veré en cualquier parte. A mi madre, que no logro sentir lejos, iré a buscarla al mar. No pondré flores sobre sus cenizas. Voy a ver si pongo estrellas.

Punto final: Estaré fuera hasta el tres de noviembre. Los podré leer, pero no escribiré. Un beso a todos.

Las mujeres de Mastretta...

Un saludo Afectuoso

Luisa Adriana C.

COLOMBIA ES PASION

"Quiero estar dónde esté mi sombra si es ahí donde estarán tus ojos".JOSE SARAMAGO

Cuentos Históricos del Pueblo Africano - Johari Gautier Carmona

Trabajo en equipo con Nagore.

África es un continente abundante en soñadores, leyendas, tradición y sabiduría; una tierra mágica. A menudo pensamos que sólo es un continente vasto y vacío, sin historia y totalmente dependiente de los avances occidentales. Son ideas que se repiten y que se nutren de otras preconcebidas; pero, ¿sabía que África llegó a ser la máxima potencia de todos los tiempos gracias a la ciencia de los egipcios? ¿Sabía que el Imperio de Malí fue uno de los más ricos jamás conocidos y que uno de sus dirigentes trató de cruzar el océano Atlántico doscientos años antes de que lo hiciera Cristóbal Colón? ¿Alguien le comentó alguna vez que el Imperio de Songhai llegó a ser más grande y próspero que el de Alejandro Magno o que la Etiopía de Menelik II siempre permaneció libre pese a la presión colonialista de Italia? Este libro de relatos lo acercará a la realidad de África, una realidad que sobrepasa con creces el mito.

JOHARI GAUTIER CARMONA (1979) es un narrador español nacido en París. Reside actualmente en Barcelona. Es miembro del Centro de Estudios Africanos, amante de las experiencias culturales y ferviente defensor de la dignidad africana (la cual considera un elemento fundamental de su identidad). Ha cursado un postgrado sobre las sociedades africanas y escribe en distintos medios artículos sobre África y el Caribe. La escritura representa para él un modo de conciliar la riqueza de sus raíces caribeñas y españolas. Autor de la novela El Rey del mambo (2009) también ha publicado cuentos de ficción en antologías como Qué me estás contando e Historias Verdaderas. Ha sido ganador del premio «Relatos de viaje», organizado por Ediciones del viento y vagamundos.net.

http://www.4shared.com/file/wQR_fbBl/Gautier_Carmona_Johari_-_Cuent.html

[Se han eliminado los trozos de este mensaje que no contenían texto]

Quijote interactivo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mOiWQL9eVfk

El

Quijote interactivo es un proyecto que permite un acercamiento

innovador a la primera edición de la obra cumbre de Cervantes,

conservada en los fondos de la Biblioteca Nacional de España. Gracias a

esta iniciativa es posible disfrutar del Quijote como si tuviera el

libro en sus manos, al tiempo que se puede acceder a contenidos

multimedia que ayudan a contextualizar la obra.

para ver el libro:

http://quijote.bne.es

[Se han eliminado los trozos de este mensaje que no contenían texto]

Mario varas Llosa y las conejitas. Escribio para Playboy

Hugh Hefner también destacó el Nobel de Literatura a Mario Vargas Llosa

El magnate de Playboy mencionó en su Twitter el galardón otorgado al escritor peruano

No solo personajes de la cultura, política, deporte y espectáculo celebran el Nobel a Mario Vargas Llosa. En el mundo del entretenimiento para adultos también hay espacio para el reconocimiento al escritor.

El ícono de Playboy mencionó en su Twitter el galardón al peruano: "Mario Vargas Llosa ha ganado el Premio Nobel de Literatura".

Asimismo -aunque no precisó alguna fecha de publicación- destacó que el novelista haya colaborado con su publicación: "Eso lo convierte en el decimotercer escritor de Playboy que ha logrado dicho premio".

El sueno del Celta

Medio millón de ejemplares de "El sueño del celta" saldrán a la venta el 3 de noviembre

Alfaguara duplicó la producción de la nueva obra de Mario Vargas Llosa luego de que el escritor peruano ganara el Premio Nobel de Literatura 2010

Medio millón de ejemplares de "El sueño del celta", la más reciente novela de Mario Vargas Llosa, saldrán a la venta el próximo 3 de noviembre en España y América Latina, informó la empresa editorial Alfaguara.

Las copias de la novela, que narra la vida del revolucionario irlandés Sir Roger Casement, han comenzado ya a salir de la imprenta para estar en los puntos de venta la próxima semana.

Pilar Reyes, directora editorial de Alfaguara, indicó que imprimir de salida 250.000 ejemplares para España (la otra mitad irá a Latinoamperica) es una "tirada ambiciosa" y permitirá cubrir el canal de manera importante en los próximos meses.

En la imprenta donde están saliendo ya los primeros ejemplares de la novela, Pilar Reyes explicó que Vargas Llosa es una "apuesta global para la editorial" y tras la concesión del Nobel de Literatura 2010 han empezado a percibir por parte de los lectores una "emoción" "muy grande" por todos los títulos del autor.

Mario Vargas Llosa presentará su nueva novela en una conferencia de prensa en Madrid el próximo 3 de noviembre.

LOS NÚMERO DE "EL SUEÑO DEL CELTA"

442 páginas.

138.923 palabras.

1.484 párrafos.

10.842 líneas.

160.000 kilos de papel (para 500.000 ejemplares).

470 horas de impresión.

902 kilos de tinta.

900.000 metros de hilo de encuadernación.

1.000 kilos de kola para encuadernación.

Se acerca la muerte

Mario Vargas LLosa: "Me acerco a la muerte sin pensar en ella, sin temerle"

El notable escritor peruano, reciente ganador del Premio Nobel de Literatura, asegura que no le aterroriza la vejez ya que el trabajo lo vuelve "invulnerable"

El diario español El País ha publicado hoy un espléndido reportaje sobre los últimos veinte años en la vida del escritor peruano, desde aquella derrota en las elecciones de 1990 al Nobel de este 2010. Para ello ha contado con la participación del mismo Mario Vargas Llosa y de sus tres hijos: Álvaro, Gonzalo y Morgana. En la nota, el novelista de 74 años, habla su eterna pasión por la escritura, su mejor antídoto para seguir produciendo literatura y periodismo.

"No pienso parar (...) mientras tenga ilusión y curiosidad y me funcione la cabeza, que de momento creo que me sigue funcionando. La vejez no me aterroriza mientras pueda seguir desplazándome. Me acerco a la muerte sin pensar en ella, sin temerle. Mientras trabajo me siento invulnerable".

Sobre aquellas elecciones presidenciales, Vargas Llosa dice: "Un escritor tiene la ventaja de que puede convertir un fracaso en materia literaria, y eso lo alivia. La escritura es una venganza, un desquite de la vida".

Lea todo el reportaje La escritura es una venganza…un desquite de la vida.

Lea la columna de MVLL hoy en El Comercio: Las caras del Tea Party

Cunta regresiva

Mario Vargas Llosa en cuenta regresiva para recibir el Premio Nobel

A pocos días del lanzamiento de "El sueño del celta", su más reciente novela, El Comercio conversó con el escritor nacional en Nueva York. Agradece las muestras de cariño y busca tiempo para retomar su rutina y preparar el discurso que dará el 10 de diciembre en Suecia

Por Carlo Trivelli

NUEVA YORK. Todavía no ha terminado de recibir felicitaciones por el Nobel. En la bandeja de entrada de su correo electrónico quedan aún centenares de mensajes por leer. "Patricia está que se vuelve loca con tantos correos. Habría que formar una cooperativa de amigos para que me ayuden a leerlos", dice, sonriendo, Mario Vargas Llosa, quien nos recibe en su departamento en Manhattan, apenas a unas cuadras de Columbus Circle, en el lado sur de Central Park.

A pesar de todo, la sorpresa por el modo inesperado en que se le otorgó el premio sigue a flor de piel. Y el agobio que le han causado las consecuencias del Nobel: "Estoy ya sin voz después de dar tantas entrevistas. Además, me ha caído todo al mismo tiempo, porque es un período de clases en la universidad de Princeton y está mi última novela. Así que ahora viene la paliza de España con la salida del libro. Estoy yendo dentro de unos días. Y después vendrá la paliza de Estocolmo y ahí ya supongo que comienzan a calmarse las aguas", dice con tono de alivio.

Pero lo esencial de su estado de ánimo es la complacencia. Por el logro que significa el premio, claro está, pero sobre todo por las manifestaciones de cariño que ha recibido, "algunas de amigos que no veo hace siglos, que no sabía dónde estaban. Compañeros de colegio de La Salle, en Bolivia, muchos compañeros del Leoncio Prado, del colegio San Miguel de Piura donde yo terminé… gente a la que le había perdido por completo la pista. Y también son muy conmovedoras las felicitaciones de gentes anónimas, de gentes que no conozco, que se han alegrado con el premio y mandan cartas o e-mails muy cariñosos. La verdad que ha sido muy emocionante, sobre todo la magnitud, que nunca me imaginé", nos cuenta.

Le espera un programa sumamente apretado en Estocolmo, en la semana previa a la ceremonia de entrega del Nobel el próximo 10 de diciembre. Él lo sabe y lo acepta con la esperanza de que, después de eso, pueda volver a instalarse en su amada rutina de escritor. Del representante de la Academia Sueca ha recibido una carta que él ha descrito como "muy cariñosa". "Me dice que hace ya mucho tiempo que yo figuraba entre los candidatos. Una frase general, pero afirmando que no ha sido algo súbito, que ya de alguna manera había sido considerado en el pasado", justo lo contrario a la sensación que ha tenido el mundo, y el propio Vargas Llosa, que sigue hablando de la sorpresa que significó el que le otorgaran el premio.

Sobre las razones para merecer el Nobel, dice estar de acuerdo con la única declaración de motivos que conoce: "La única razón que he visto es esa frase: 'la cartografía del poder, la defensa del individuo…'. Pues, bueno, supongo que es cierto eso; en mis libros hay eso también. Yo creo que es una buena síntesis", dice. Pero algo parece quedarse en el aire. Intentamos que nos explicara qué piensa más allá de eso, pero con su seriedad y transparencia características dice que para él es un misterio. "Es una especie de secreto tan bien guardado…", dice, y añade: "y estoy seguro de que tampoco voy a averiguar nada en Estocolmo".

Pero detrás de ese discurso, en la seguridad de este líder de opinión que ha sido calificado por tantos en estos días como una de las conciencias de nuestro tiempo, uno adivina que es cierta modestia la que le impide plantearse que han sido las apuestas correctas y el compromiso con una manera de entender la literatura (también) como ejercicio cívico lo que ha motivado este merecido Nobel. Es algo que sale a la luz entre líneas, pero que definitivamente está ahí, para quien lea con atención. Es algo que con seguridad se aclarará en el discurso que dé Vargas Llosa en Estocolmo en diciembre, uno que, hasta ahora, no ha tenido tiempo de preparar.

Y ahora que ya tiene un poco más de perspectiva, ¿cómo ve el haber recibido el Nobel?

Bueno, ha sido una gran sorpresa. Es una cosa que se suele decir de una manera convencional, pero te aseguro que en mi caso no es nada convencional.

Y más allá de la sorpresa…

Hombre, pues, muy grato. Es un reconocimiento importante y además una gran promoción para los libros. Ha sido muy conmovedor. Sobre todo la cosa en el Perú me ha tocado mucho porque –como me decía Nélida Piñón– al final lo que ocurre en tu tierra es lo que te afecta más, o para bien o para mal (ver recuadro "Nacionalismo"). Pero incluso sabiendo eso, a mí me ha sorprendido la repercusión mediática que ha habido.

Pero la repercusión también tiene que ver con la figura pública y política que es usted. Con el hecho de que es un Nobel a un escritor de habla hispana, que, además, ha tenido mucho éxito y que hace tiempo que se esperaba que lo ganara.

Bueno, no se daba a un hispanohablante desde el premio a Octavio Paz en 1990… Y como yo he estado metido en política, aunque de eso ya hace muchos años, eso sale inmediatamente a flote. No sé, la verdad, no me atrevo a darte una opinión sobre eso.

Me refería a que es usted un escritor con ideas políticas muy claras.

Bueno, yo opino que eso forma parte del trabajo de un escritor. Yo no creo que un escritor pueda exonerarse de algo que es responsabilidad de todos los ciudadanos. Si quieres que en tu país haya democracia, lo menos que se te puede pedir es que participes, que no te vuelvas de espalda frente a lo que está pasando, que opines. En las democracias no, como hay unos canales por donde se expresan las críticas, donde hay una oposición que es respetada, muchos escritores se desinteresan de la política, y eso no les impide hacer buena literatura. Pero yo te diría que en un continente como el latinoamericano, es hasta una inmoralidad que un escritor diga: "Yo no; a mí la política no me interesa nada". Yo creo que si tú no participas, no tienes derecho a protestar. En todo caso, es lo que practico haciendo periodismo.

En sus novelas eso también está presente…

Es que tampoco me gusta la idea del escritor completamente separado de lo que pasa en la calle. Pero ese es un tema muy controvertido y, además, soy muy consciente de que es peligrosísimo acercar mucho la literatura a la política, porque la literatura se puede convertir en propaganda, en un instrumento para difundir ideas políticas, y eso mata la literatura. Esta debe tener una perspectiva más larga, más ancha que la de la actualidad.

¿Y dónde marcar la línea divisoria?

No hay línea divisoria; es muy fluida. Hay novelas políticas extraordinarias a las que no se les puede acusar de no ser literarias. Yo recuerdo una de las novelas políticas más impresionantes que he leído: "La marcha Radetzky", de Joseph Brodsky, un escritor austriaco. Es una novela extraordinaria sobre el fin del Imperio Austro-Húngaro. Él escribió muy claramente pensando en una actualidad y, sin embargo, la novela trasciende esa actualidad y vale para cualquier país. Es un caso interesantísimo. No hay muchos, pero hay algunos: yo admiro muchísimo "La condición humana", de Malraux, una novela clarísimamente política.

Bueno, y sus novelas…

Y mis novelas también, claro. Pero yo creo que –digamos– en las novelas más políticas que he escrito, he hecho todo lo posible para que no tengan que ser cotejadas con la realidad histórica para ser entendidas con libertad. Siempre he procurado eso. Yo creo que la novela tiene que tratar de abarcar algo más permanente que la actualidad política.

Entonces, ¿para salvar la novela de la política hay que darle esa perspectiva totalizante que usted busca?

Exactamente. Tiene que estar la política enlazada con otros tipos de actividades, con la vida social y la del individuo, de las que la política es una parte, a veces importante, pero nunca del todo. Hombre, yo lo que he querido hacer en muchas de mis novelas, como en "Conversación en La Catedral", ha sido más bien mostrar cómo la política, cierto tipo de política, como la de un régimen dictatorial, se infiltra en las vidas de las personas y las invade, las deteriora, las corrompe y puede llegar a destruirlas completamente. Y yo creo que es la tragedia de América Latina. Las dictaduras son las que han convertido a América Latina en un continente muy atrasado, que ha estado perdiendo oportunidades con respecto al resto del mundo.

Esa sensación acerca de América Latina respecto al Perú ha cambiado mucho en los últimos años. ¿Cómo ve al Perú ahora?

Pues con cierto optimismo. Yo creo que el Perú está viviendo una muy buena época, lo cual no quiere decir que no haya problemas. Pero fíjate: ya llevamos 10 años de gobiernos democráticos, de una institucionalidad democrática que está funcionando, de un desarrollo económico muy elevado. Y todo indica que debería mantenerse y crecer, si no cometemos la insensatez de salirnos de ese cuadro: democracia política, economía de mercado, apertura al mundo; eso nos ha traído muy buenos resultados.

En función de eso, ¿cómo ve las próximas elecciones?

Yo las veo con optimismo. Creo que hay unos consensos en el Perú que no van a permitir que haya una marcha atrás. Tengo la impresión de que eso es lo que está ocurriendo y, por eso, creo que hay que ser optimistas. Sin caer en ninguna forma de complacencia, porque ya hemos visto la historia y las sorpresas que podemos llevarnos. La complacencia es muy peligrosa, siempre; creer que ya llegamos y nos dormimos (sonríe). No hemos llegado, falta mucho.

EL PRÓXIMO LIBRO

La cultura del espectáculo

El ajetreo del Nobel ha retrasado el trabajo de Vargas Llosa en su próximo libro, una visión crítica de la sociedad actual en la que denuncia lo que él llama "La cultural del espectáculo". "Ya tenía tres borradores de capítulos avanzados, pero desgraciadamente se ha quedado paralizado eso con todo este trajín. Espero retomarlo ahora que se calmen un poco las aguas", nos dice. La idea central de este futuro trabajo es que, si bien en la actualidad hay mucha producción cultural y esta se ha difundido en la vida contemporánea más que en el pasado, al mismo tiempo es una cultura mucho más superficial, más frívola y donde hay mucho menos jerarquías reconocidas. "En nuestra época es difícil saber qué cosa es importante, qué cosa es superficial, qué cosa es un gran artista, quién es un gran embaucador, porque la frivolidad ha entrado y ha distorsionado completamente las tablas de valores", explica el Nobel.

RAZONES DE UN PERUANO UNIVERSAL

La gran diferencia entre patriotismo y nacionalismo

Luego de los intentos de cierto gobierno por desarraigarlo del Perú y de los infaltables comentarios malintencionados acerca de su vocación universal y su crítica a los nacionalismos, mucho se sorprendieron cuando Mario Vargas Llosa afirmó "Yo soy el Perú", en la recordada conferencia de prensa en el instituto Cervantes de Manhattan. Aquí, una prístina aclaración del Nobel.

"No hay que confundir el nacionalismo con el patriotismo. Este es un sentimiento generoso, no es un sentimiento contra nadie, mientas que el nacionalismo es un sentimiento hostil contra el otro, que convierte en un valor una circunstancia -digamos- accidental, que es el lugar de nacimiento. Eso es un disparate, porque las gentes deben valer por lo que hacen y no por dónde nacen, ni por la raza que tienen, y el nacionalismo es una forma disimulada de racismo. Nada ha hecho correr tanta sangre en la historia como el nacionalismo: las guerras mundiales, las carnicerías del Medio Oriente. Ahora, que uno ame al país donde nació, donde creció, el país de sus ancestros, que uno tenga un cariño especial por los paisajes, por una cierta manera de hablar, un tipo de sensibilidad, eso es un sentimiento generoso y desde luego no solamente lo defiendo, sino que también lo vivo, lo siento. Creo que es una distinción que hay que hacer si queremos librarnos de esos estragos que ha causado el nacionalismo".

SE LANZA EL 3 DE NOVIEMBRE

Ya llega "El sueño del celta"

Entre los apuros que lo obligan a romper su tan querida rutina en estas semanas, está el que Vargas Llosa tenga que volar a España esta semana para el tan esperado lanzamiento, este miércoles 3 de noviembre, de "El sueño del celta", su más reciente novela.

Como le ha pasado otras veces, Vargas Llosa fue entrando en el mundo de su novela casi sin darse cuenta. Supo de la existencia de su protagonista, Roger Casement, gracias a una biografía de Joseph Conrad, el autor de la célebre "El corazón de las tinieblas", novela que encuentra en las atrocidades de la expansión colonial en el Congo, la viva imagen del mal encarnado en las ansias de progreso del hombre blanco del siglo XIX. "Ellos fueron muy amigos. La primera persona que Conrad conoce cuando va al Congo es Casement. Y él le abre los ojos, le muestra lo que realmente ocurría en el Congo. Y de ahí sale "El corazón de las tinieblas". Hay cartas en que le dice a Casemet: "ese libro jamás lo hubiera escrito sin haberlo conocido a usted y sin haber escuchado las cosas que usted me contó y me mostró en el Congo". Me dio mucha curiosidad, porque vi que había sido una persona muy importante en la época del caucho por su denuncia de las atrocidades que se cometían y vi que había estado en el Perú. Y así, sin pensar en escribir sobre eso, empecé a seguirle la pista", explica Vargas Llosa. "Y de pronto me di cuenta -como creo que me ha ocurrido en casi todas las novelas- de que me había puesto a trabajar sin haberlo planeado desde un principio".

El trabajo en la novela lo llevó a conocer realidades que le eran ajenas, como las del Congo colonial y el mundo de Irlanda y sus luchas independentistas. "Casement fue uno de esos irlandeses que se convirtieron en defensores del Imperio Británico, de la integración de Irlanda con Inglaterra y que, luego, comenzaron a tomar distancia y a buscar la independencia. A mí me fascinó en Casement la doble o triple vida que llevó. Por una parte, como diplomático británico, sirvió al imperio; pero al mismo tiempo trabajó de una manera muy dedicada y comprometida para denunciar los horrores que se cometían, para combatir la colonización, es decir, justamente la idea del imperio. Y luego está su vida más privada (más secreta), que es su vida sexual, una que debió obligarlo a vivir en una tensión terrible y permanente en una época en que había una moral muy estricta, en que la homosexualidad se castigaba con la cárcel [era un crimen mayor]", explica.

Con todo, luego de la investigación, "quedaba mucho de Roger Casement para inventar. El personaje se prestaba mucho para crear una novela". Así, como con "Conversación en La Catedral" o "La guerra del fin del mundo", estamos ante otra gran obra con el sello Vargas Llosa.

sábado, 30 de octubre de 2010

el libro no está por morir

Este artículo apoya la idea de la supervivencia del libro (digital o papel)

http://www.lanacion.com.ar/nota.asp?nota_id=1318380

con algunas afirmaciones interesantes:

"Pero tenemos que ser sinceros. Al menos una vez. Al libro no lo está matando el cine. Ni Internet. Ni el teatro. Ni la televisión. Ni los e-books. Ni siquiera la piratería. Al libro lo está matando la gente que proclama que el libro es mejor cuando nunca leyó el libro. Los que se amparan en esa perogrullada, en ese paraguas enorme cobija-charlatanes, en esa frase hecha incuestionable que en el fondo, no dice nada. Así que ya basta con la muerte del libro, que al libro el mundo audiovisual no le ha hecho nada. Son ellos, los que acuñan esa frase idiota, los que están haciendo el trabajo sucio. Ahora mismo, sin ir más lejos, quizás haya uno aquí, agazapado y listo para reenviarle esta columna a un amigo cuando ni siquiera la terminó de leer."

Bueno, me agazapo y lo leo con detenimiento.

Valga un pequeño comentario: creo que a veces sucede al contrario, que es al revés, que el cine o la televisión, pueden propulsar un libro o un autor.

Hace ya unos cuantos años, en una telenovela, cuyo título desconozco, por ser un género del que no tengo la mínima atracción, recitaban los actores (que ya olvidé sus nombres)a lo largo del melodrama los versos de una poetisa, que luego fue un boom de ventas. ¿Julia Prilutzki Farny? Ya lo olvidé, no estoy seguro que haya sido así.

Saludos

Julio A

viernes, 29 de octubre de 2010

1984

Nineteen Eighty-Four

| Nineteen Eighty-Four | |

|---|---|

British first edition cover | |

| Author | George Orwell |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Dystopian, political fiction, social science fiction |

| Publisher | Secker and Warburg (London) |

| Publication date | 8 June 1949 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover & Paperback) & e-book, audio-CD |

| Pages | 326 pp (Paperback edition) |

| OCLC Number | 52187275 |

| Dewey Decimal | 823/.912 22 |

| LC Classification | PR6029.R8 N647 2003 |

Nineteen Eighty-Four (sometimes written 1984) is a 1949 dystopian novel by George Orwell about an oligarchical, collectivist society. Life in the Oceanian province of Airstrip One is a world of perpetual war, pervasive government surveillance, and incessant public mind control. The individual is always subordinated to the state, and it is in part this philosophy which allows the Party to manipulate and control humanity. In the Ministry of Truth (Minitrue, in Newspeak), protagonist Winston Smith is a civil servant responsible for perpetuating the Party's propaganda by revising historical records to render the Party omniscient and always correct, yet his meagre existence disillusions him to the point of seeking rebellion against Big Brother, eventually leading to his arrest, torture, and conversion.

As literary political fiction, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a classic novel of the social science fiction subgenre. Since its publication in 1949, many of its terms and concepts, such as Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak, and Memory hole, have become contemporary vernacular. In addition, the novel popularized the adjective Orwellian, which refers to propaganda, lies, or manipulation of the past in the service of a totalitarian agenda.

| |

[edit] History and title

George Orwell "encapsulate[d] the thesis at the heart of his unforgiving novel" in 1944, then wrote most of it on the island of Jura, Scotland, during the 1947–48 period, despite being critically tubercular.[1] On 4 December 1948, he sent the final manuscript to the Secker and Warburg editorial house who published Nineteen Eighty-Four on 8 June 1949;[2][3] by 1989, it had been translated to more than 65 languages, then the greatest number for any novel.[4] The title of the novel, its terms, its Newspeak language, and the author's surname are contemporary bywords for privacy lost to the state, and the adjective Orwellian connotes totalitarian thought and action in controlling and subjugating people. Newspeak language says the opposite of what it means by misnomer; hence the Ministry of Peace (Minipax) deals with war, and the Ministry of Love (Miniluv) deals with torture.

The Last Man in Europe was one of the original titles for the novel, but, in a 22 October 1948, letter to publisher Frederic Warburg, eight months before publication, Orwell wrote him about hesitating between The Last Man in Europe and Nineteen Eighty-Four;[5] yet Warburg suggested changing the Man title to one more commercial.[6] Speculation about Orwell's choice of title includes perhaps an allusion to the 1884 founding centenary of the socialist Fabian Society,[7] or to the novels The Iron Heel (1908), by Jack London, or to The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), by G. K. Chesterton, both of which occur in 1984,[8] or to the poem "End of the Century, 1984", by Eileen O'Shaughnessy, his first wife.

Moreover, in the novel 1985 (1978), Anthony Burgess proposes that Orwell, disillusioned by the Cold War's onset, intended to title the book 1948. The introduction to the Penguin Books Modern Classics edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four, reports that Orwell originally set 1980 as the story's time, but the extended writing led to re-titling the novel, first, to 1982, then to 1984, because it is an inversion of the 1948 composition year.[9] Nineteen Eighty-Four has been, at times in its history, either banned or legally challenged as intellectually dangerous to the public, just like Brave New World (1932), by Aldous Huxley; We (1924), by Yevgeny Zamyatin; Kallocain (1940), by Karin Boye; and Fahrenheit 451 (1951), by Ray Bradbury.[10] In 2005, Time magazine included it in its list of one hundred best English-language novels since 1923.[11]

[edit] Copyright status

Nineteen Eighty-Four will not enter the US public domain until 2044,[12] and in the European Union until 2020, although it is in the public domain in Canada,[13] Russia,[14] South Africa,[15] and Australia.[16] On July 17, 2009, Amazon.com withdrew certain Amazon Kindle titles, including Nineteen Eighty-Four, from sale, refunded buyers, and removed the items from the Amazon Store after discovering that the publisher lacked rights to publish the titles in question.[17] After this removal, upon syncing with their Amazon libraries, items from purchasers' devices were likewise "removed" due to the syncing process. Notes and annotations for the books made by users on their devices were also deleted.[18] After the move prompted outcry and comparisons to Nineteen Eighty-Four itself, Amazon spokesman Drew Herdener stated that the company is "[c]hanging our systems so that in the future we will not remove books from customers' devices in these circumstances."[19]

[edit] Intentions

In the essay "Why I Write" (1946), Orwell described himself as a Democratic Socialist.[20] Thus, in his 16 June 1949 letter to Francis Henson of the United Automobile Workers about the excerpts published in Life (25 July 1949) magazine and The New York Times Book Review (31 July 1949), Orwell said:

My recent novel [Nineteen Eighty-Four] is NOT intended as an attack on Socialism or on the British Labour Party (of which I am a supporter), but as a show-up of the perversions . . . which have already been partly realized in Communism and Fascism. . . . The scene of the book is laid in Britain in order to emphasize that the English-speaking races are not innately better than anyone else, and that totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere.—Collected Essays [21]

[edit] Background

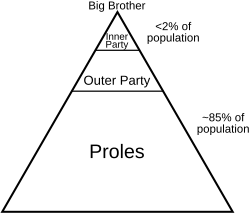

Nineteen Eighty-Four occurs in Oceania, one of three intercontinental super-states who divided the world among themselves after a global war. In London, the "chief city of Airstrip One",[22] the Oceanic province that "had once been called England or Britain".[23] Posters of the Party leader, Big Brother, bearing the caption BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU dominate the landscape, while the telescreen (transceiving television) ubiquitously monitors the private and public lives of the populace. The social class system is threefold: (I) the upper-class Inner Party, (II) the middle-class Outer Party, and (III) the lower-class Proles (from Proletariat), who make up 85% of the population and represent the working class. As the government, the Party controls the population via four government ministries: the Ministry of Peace, Ministry of Plenty, Ministry of Love, and the Ministry of Truth, where protagonist Winston Smith (a member of the Outer Party), works as an editor revising historical records to concord the past to the contemporary party line orthodoxy—that changes daily—and deletes the official existence of people identified as unpersons.

Winston Smith's story begins on 4 April 1984: "It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen";[24] yet the date is dubitable, because it is what he perceives, given the continual historical revisionism; he later concludes it is irrelevant. Winston's memories and his reading of the proscribed book, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, by Emmanuel Goldstein, reveal that after the Second World War, the United Kingdom fell to civil war and then was integrated into Oceania. Simultaneously, the USSR's annexation of continental Europe established the second superstate of Eurasia. The third superstate, Eastasia, represents East and Southeast Asian region. The three superstates fight a perpetual war for the remaining unconquered lands of the world; they form and break alliances as convenient.

From his childhood (1949–53), Winston remembers the Atomic Wars fought in Europe, western Russia, and North America. It is unclear to him what occurred first—either the Party's civil war ascendance, or the US's British Empire annexation, or the war wherein Colchester was bombed—however, the increasing clarity of his memory and the story of his family's dissolution suggest that the atomic bombings occurred first (the Smiths took refuge in a tube station) followed by civil war featuring "confused street fighting in London itself", and the societal postwar reorganisation, which the Party retrospectively call "the Revolution".

[edit] Plot

The story of Winston Smith presents the world in the year 1984, after a global atomic war, via his perception of life in Airstrip One (England or Britain), a province of Oceania, one of the world's three superstates; his intellectual rebellion against the Party and illicit romance with Julia; and his consequent imprisonment, interrogation, torture, and re-education by the Thinkpol in the Miniluv.

[edit] Winston Smith

Winston Smith is an intellectual, a member of the Outer Party, who lives in the ruins of London, and who grew up in the post–Second World War UK, during the revolution and the civil war after which the Party assumed power. During the civil war, the Ingsoc movement placed him in an orphanage for training and subsequent employment as a civil servant. Yet, his squalid existence is living in a one-room apartment, a subsistence diet of black bread and synthetic meals washed down with Victory-brand gin. He keeps a journal of negative thoughts and opinions about the Party and Big Brother, which, if discovered by the Thought Police, would warrant death. Moreover, he is fortunate, because the apartment has an alcove, beside the telescreen, where it cannot see him, where he believes his thoughts remain private, whilst writing in his journal: "Thoughtcrime does not entail death. Thoughtcrime IS death". The telescreens (in every public area, and the quarters of the Party's members), hidden microphones, and informers permit the Thought Police to spy upon everyone and so identify anyone who might endanger the Party's régime; children most of all, are indoctrinated to spy and inform on suspected thought-criminals—especially their parents.

At the Minitrue, Winston is an editor responsible for the historical revisionism concording the past to the Party's contemporary official version of the past; thus making the government of Oceania seem omniscient. As such, he perpetually rewrites records and alters photographs, rendering the deleted people as unpersons; the original document is incinerated in a memory hole. Despite enjoying the intellectual challenge of historical revisionism, he is fascinated by the true past, and eagerly tries to learn more about it.

[edit] Julia

One day, at the Minitrue, whilst Winston is assisting a woman who had fallen, she surreptitiously hands him a note reading "I LOVE YOU"; she is "Julia", a dark-haired mechanic who repairs the ministry's novel-writing machines. Before then, he had loathed her, presuming she was a fanatical member of the Junior Anti-Sex League, given she wears the league's red sash, symbolising puritanical renouncement of sexual intercourse, yet his hostility vanishes upon reading her note. Afterwards, they begin a love affair, meeting first in the country, then in a rented room atop an antiques shop in a proletarian London neighborhood, where they think they are safe and alone; unbeknownst to Winston, the Thought Police have discovered their rebellion and had been spying on them for some time.

Later, when Inner Party member O'Brien approaches him, he believes the Brotherhood have communicated with him. Under the pretext of giving him a copy of the latest edition of the Newspeak dictionary, O'Brien gives him "the book", The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, said to have been written by Emmanuel Goldstein, leader of the Brotherhood, which explains the perpetual war and the slogans, WAR IS PEACE, FREEDOM IS SLAVERY, and IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH.

[edit] Capture

The Thought Police captures Winston and Julia in their bedroom, to be delivered to the Ministry of Love for interrogation, and Charrington, the shop keeper who rented the room to them, reveals himself as an officer in the Thought Police. After a prolonged regimen of systematic beatings and psychologically draining interrogation by Party ideologues, O'Brien tortures Winston with electroshock, telling him it will cure him of his insanity—his manifest hatred for the Party. In long, complex conversation, he explains that the Inner Party's motivation: complete and absolute power. Asked if the Brotherhood exists, O'Brien replies that Winston will never know whilst alive; it will remain an unsolvable riddle in his mind. During a torture session, his imprisonment in the Miniluv is explained: "There are three stages in your reintegration," said O'Brien. "There is learning, there is understanding, and there is acceptance" of the Party's reality.

[edit] Confession and betrayal

During political re-education, Winston admits to and confesses his crimes and to crimes he did not commit, implicating others and his beloved Julia. In the second stage of re-education for reintegration, O'Brien makes Winston understand he is "rotting away". Countering that the Party cannot win, Winston admits: "I have not betrayed Julia". O'Brien understands that despite his criminal confession and implication of Julia, Winston has not betrayed her in that he "had not stopped loving her; his feeling toward her had remained the same".

One night in his cell Winston suddenly awakens, screaming: "Julia! Julia! Julia, my love! Julia!", whereupon O'Brien rushes in, not to interrogate but to send him to Room 101, the Miniluv's most feared room where resides the worst thing in the world. There, the prisoner's greatest fear is forced on them; the final step in political re-education: acceptance. Winston's primal fear of rats is imposed upon him as a wire cage holding hungry rats that will be fitted to his face. When the rats are about to devour his face, he frantically shouts: "Do it to Julia!" - in his moment of fear, ultimately relinquishing his love for Julia. The torture ends and Winston is reintegrated to society, brainwashed to accept the Party's doctrine and to love Big Brother.

During Winston's re-education, O'Brien always understands Winston's thoughts, it seems that he always speaks what Winston is thinking at the time.

[edit] Re-encountering Julia

After reintegration to Oceanian society, Winston encounters Julia in a park where each admits having betrayed the other and that betrayal changes a person:

"I betrayed you," she said baldly.

"I betrayed you," he said.

She gave him another quick look of dislike.

"Sometimes," she said, "they threaten you with something—something you can't stand up to, can't even think about. And then you say, 'Don't do it to me, do it to somebody else, do it to so-and-so.' And perhaps you might pretend, afterwards, that it was only a trick and that you just said it to make them stop and didn't really mean it. But that isn't true. At the time when it happens you do mean it. You think there's no other way of saving yourself and you're quite ready to save yourself that way. You want it to happen to the other person. You don't give a damn what they suffer. All you care about is yourself."

"All you care about is yourself," he echoed.

"And after that, you don't feel the same toward the other person any longer."

"No," he said, "you don't feel the same."

Throughout, a score recurs in Winston's mind:

Under the spreading chestnut tree

I sold you and you sold me—

The lyric is an ambiguous bastardization of a Glen Miller lyric, which in form has many sinister implications.[25]

[edit] Capitulation and conversion

Winston Smith, now an alcoholic reconciled to his impending execution, has accepted the Party's depiction of life, and sincerely celebrates a news bulletin reporting Oceania's decisive victory over Eurasia. He then realizes that he had won the victory over himself. "He loved Big Brother".

[edit] Characters

[edit] Principal characters

- Winston Smith — the protagonist is a phlegmatic everyman.

- Julia — Winston's lover is a covert "rebel from the waist downwards" who espouses Party doctrines whilst living contrarily.

- Big Brother — the dark-eyed, mustachioed embodiment of the Party governing Oceania (viz. Joseph Stalin), whom few people have seen, if anyone. There is doubt as to whether he exists.

- O'Brien — the antagonist, a member of the Inner Party who deceives Winston and Julia that he is of the Brotherhood resistance.

- Emmanuel Goldstein — a former Party leader, bespectacled and with a goatee beard like the Soviet revolutionary Leon Trotsky (an original leader of the Bolshevik Revolution whose real last name was Bronstein and who, after losing to Stalin in the struggle for power, was deported from the USSR and after some years writing against the Soviet regime was eventually murdered). Goldstein's persona is as an enemy of the state - the national nemesis used to ideologically unite Oceanians with the Party, purported author of "the book" (The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism), and leader of the Brotherhood. The Book was actually created and collaborated on by O'Brien. Goldstein allows the Party to encourage Two Minutes Hate and other fear mongering.

Note that it is never made clear in the novel if either Big Brother or Emmanuel Goldstein actually exist.

[edit] Secondary characters

- Aaronson, Jones and Rutherford — Former Inner Party members. Winston vaguely remembers that they had been among the original leaders of the Revolution, long before "Big Brother" had been heard of. They were tortured into confessing to absurd crimes and then executed in the purges of the 1960s (analogous to the Soviet Purges of the 1930s, in which leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution such as Kamenev and Zinoviev were similarly treated). In the course of his work, Winston finds newspaper evidence proving their innocence and hastily destroys it (in the 1984 film version he finds an old bottle of gin bearing their portraits on the label, from when they had been leading members of the regime).

- Ampleforth — Winston's Records Department colleague imprisoned for leaving the word "God" in a Kipling poem; Winston meets him again in the Miniluv. Ampleforth is a dreamer and an intellectual who takes pleasure from his work and seems to treat poetry and language with respect. This is his undoing as it interferes with his work and causes him to displease the Party.

- Charrington — An officer of the Thought Police posing as an antiques-shop keeper.

- Katharine — The indifferent wife whom Winston "can't get rid of". Despite disliking sexual intercourse with him, she continued because it was their "duty to the Party". She is a "goodthinkful" ideologue. At some point before the novel begins, Katharine and Winston were separated as they were not able to produce children.

- Martin — O'Brien's Mongolian servant.

- Parsons — Winston's naïve neighbour and an ideal member of the Outer Party: an un-educated, suggestible man. He is utterly loyal to the Party and believes fully in its image of perfection. He is in a way like the proles, unable to see the bigger aspects of the world. He is active and participates in hikes and leads community group and fundraisers. Despite being a fool, Parsons does possess some good traits. He is a very friendly man and seems to believe in a basic form of decency despite his political views. He punishes his son for firing a catapult at Winston and shows fondness for his children despite his belief that the end of family life is a good idea. He is captured when his children claim that he repeatedly and unknowingly spoke against the Party in his sleep and he is last seen in the Ministry of Love, proud of having been betrayed by his orthodox children.

- Syme — Winston's intelligent colleague, a lexicographer developing Newspeak, whom the Party "vaporized" because he remained a lucidly-thinking intellectual. Though Syme holds orthodox opinions in line with Party doctrine, Winston notes "He is too intelligent. He sees too clearly and speaks too plainly."

[edit] The world in 1984

[edit] Ingsoc (English Socialism)

In the year 1984, Ingsoc (English Socialism), is the regnant ideology and pseudo-Philosophy of Oceania, and Newspeak is its official language.

[edit] Ministries of Oceania

In London, the Airstrip One capital city, Oceania's four government ministries are in pyramids (300 metres high), the façades of which display the Party's three slogans. The ministries' names are antonymous doublethink to their true functions: "The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation". (Part II, Chapter IX — The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism)

- Ministry of Peace (Newspeak: Minipax)

Minipax reports Oceania's perpetual war.

The primary aim of modern warfare (in accordance with the principles of doublethink, this aim is simultaneously recognized and not recognized by the directing brains of the Inner Party) is to use up the products of the machine without raising the general standard of living. Ever since the end of the nineteenth century, the problem of what to do with the surplus of consumption goods has been latent in industrial society. At present, when few human beings even have enough to eat, this problem is obviously not urgent, and it might not have become so, even if no artificial processes of destruction had been at work.

- Ministry of Plenty (Newspeak: Miniplenty)

The Ministry of Plenty rations and controls food, goods, and domestic production; every fiscal quarter, the Miniplenty publishes false claims of having raised the standard of living, when it has, in fact, reduced rations, availability, and production. The Minitrue substantiates the Miniplenty claims by revising historical records to report numbers supporting the current, "increased rations".

- Ministry of Truth (Newspeak: Minitrue)

The Ministry of Truth controls information: news, entertainment, education, and the arts. Winston Smith works in the Minitrue RecDep (Records Department), "rectifying" historical records to concord with Big Brother's current pronouncements, thus everything the Party says is true.

- Ministry of Love (Newspeak: Miniluv)

The Ministry of Love identifies, monitors, arrests, and converts real and imagined dissidents. In Winston's experience, the dissident is beaten and tortured, then, when near-broken, is sent to Room 101 to face "the worst thing in the world"—until love for Big Brother and the Party replaces dissension.

[edit] Doublethink

The keyword here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. This demands a continuous alteration of the past, made possible by the system of thought which really embraces all the rest, and which is known in Newspeak as doublethink. Doublethink is basically the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one's mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.

– Part II, Chapter IX — The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism

[edit] Political geography

Three perpetually warring totalitarian super-states, control the world:[26]

- Oceania (ideology: Ingsoc, i.e., English Socialism) comprises Great Britain, Ireland, Saveca, Australia, Polynesia, Southern Africa, and the Americas.

- Eurasia (ideology: Neo-Bolshevism) comprises continental Europe and northern Asia.

- Eastasia (ideology: Obliteration of the Self, i.e., "Death worship") comprises China, Japan, Korea, and Northern India.

The perpetual war is fought for control of the "disputed area" lying "between the frontiers of the super-states", it forms "a rough parallelogram with its corners at Tangier, Brazzaville, Darwin and Hong Kong",[26] thus northern Africa, the Middle East, southern India and south-east Asia are where the super-states capture slaves. Emmanuel Goldstein's book, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism explains that the super-states' ideologies are alike and that the public's ignorance of this fact is imperative so that they might continue believing in the detestability of the opposing ideologies. The only references to the exterior world for the Oceanian citizenry (the Outer Party and the Proles), are Minitrue maps and propaganda ensuring their belief in "the war".

[edit] The Revolution

Winston Smith's memory and Emmanuel Goldstein's book communicate some of the history that precipitated the Revolution; Eurasia was established after the Second World War (1939–45), when US and Commonwealth soldiers withdrew from continental Europe, thus the USSR conquered Europe against slight opposition. Eurasia does not include the British Empire because the US annexed it, Latin America, southern Africa, Australasia and Canada, in establishing Oceania gaining control a quarter of the planet. The annexation of Britain was part of the Atomic Wars that provoked civil war; per the Party, it was not a revolution but a coup d'état that installed a ruling élite derived from the native intelligentsia.

Eastasia, the last superstate established, comprises the Asian lands conquered by China and Japan. Although Eurasia prevented Eastasia from matching it in size, its skilled populace compensate for that handicap; despite an unclear chronology most of that global reorganisation occurred between 1945 and the 1960s.

[edit] The War

| Perpetual War | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The telescreen war: The arrows of the warring Black (Eurasian) and White (Oceanian) forces. | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

| Oceania | Eurasia | Eastasia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

| Big Brother | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

| Unknown | "Half a million prisoners" captured on conquering Africa.[27] | Unknown | ||||||||

In 1984, there is a perpetual war between Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia, the super-states which emerged from the atomic global war. "The book", The Theory and Practice of Oligarchic Collectivism by Emmanuel Goldstein, explains that each state is so strong it cannot be defeated, even with the combined forces of two super-states—despite changing alliances. To hide such contradictions, history is re-written to explain that the (new) alliance always was so; the populaces accustomed to doublethink accept it. The war is not fought in Oceanian, Eurasian or Eastasian territory but in a disputed zone comprising the sea and land from Tangiers (northern Africa) to Darwin (Australia) to the Arctic. At the start, Oceania and Eastasia are allies combatting Eurasia in northern Africa.

That alliance ends and Oceania allied with Eurasia fights Eastasia, a change which occurred during the Hate Week dedicated to creating patriotic fervour for the Party's perpetual war. The public are blind to the change; in mid-sentence an orator changes the name of the enemy from "Eurasia" to "Eastasia" without pause. When the public are enraged at noticing that the wrong flags and posters are displayed they tear them down—thus the origin of the idiom "We've always been at war with Eastasia"; later the Party claims to have captured Africa.

"The book" explains that the purpose of the unwinnable, perpetual war is to consume human labour and commodities, hence the economy of a super-state cannot support economic equality (a high standard of life) for every citizen. Goldstein also details an Oceanian strategy of attacking enemy cities with atomic rockets before invasion, yet dismisses it as unfeasible and contrary to the war's purpose; despite the atomic bombing of cities in the 1950s the super-states stopped such warfare lest it imbalance the powers. The military technology in 1984 differs little from that of the Second World War, yet strategic bomber aeroplanes were replaced with Rocket Bombs, Helicopters were heavily used as weapons of war (while they didn't figure in WW2 in any form but prototypes) and surface combat units have been all but replaced by immense and unsinkable Floating Fortresses, island-like contraptions concentrating the firepower of a whole naval task force in a single, semi-mobile platform (in the novel one is said to have been anchored between Iceland and the Faroe Islands, suggesting a preference for sea lane interdiction and denial).

[edit] Living standards

In 1984, the society of Airstrip One lives in poverty; hunger, disease and filth are the norms and ruined cities and towns the consequence of the civil war, the atomic wars and enemy (possibly Oceanian) rockets. When travelling about London rubble, social decay and wrecked buildings surround Winston Smith; other than the ministerial pyramids, little of London was rebuilt.

The standard of living of the populace is low; almost everything, especially consumer goods is scarce and available goods are of low quality; half of the Oceanian populace go barefoot—despite the Party reporting increased boot production. The Party defend the poverty as a necessary sacrifice for the war effort; "the book" reports that partly correct, because the purpose of perpetual war is consuming surplus industrial production.

The Inner Party upper class of Oceanian society enjoy the highest standard of living. The antagonist O'Brien, resides in a clean and comfortable apartment, with a pantry well stocked with quality foodstuffs (wine, coffee, sugar, etc.), denied to the general populace, the Outer Party and the Proles, who consume synthetic foodstuffs; liquor, Victory Gin and cigarettes are of low quality.[28] Winston is astonished that the lifts in O'Brien's building work and that the telescreens can be switched off. The Inner Party are attended to by slaves captured in the disputed zone; Martin, O'Brien's manservant, is Asian.

Despite the Inner Party's high standard of living, the quality of their life is inferior to pre–Revolution standards. Regarding the lower class, the Party treat the Proles as animals—they live in poverty and are kept sedated with cheap beer, pornography, and a national lottery. The Proles are freer than the members of the Party and are less intimidated than the middle class Outer Party; they jeer at the telescreens.

"The book" reports that the state of things derives from the observation that it is the middle class, not the lower class, which usually started revolutions, therefore tight control of the middle class penetrates their minds in determining their quotidian lives, and potential rebels are politically neutralized via promotion to the Inner Party; nonetheless Winston Smith believed that "the future belonged to the proles".

[edit] Themes

[edit] Nationalism

Nineteen Eighty-Four expands upon the subjects summarized in the essay Notes on Nationalism (1945)[29] about the lack of vocabulary needed to explain the unrecognized phenomena behind certain political forces. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Party's artificial, minimalist language 'Newspeak' addresses the matter.

- Positive nationalism: Oceanians' perpetual love for Big Brother, who may be long dead or even non-existent from the beginning; Celtic Nationalism, Neo-Toryism and British Israelism are (as Orwell argues) defined by love.

- Negative nationalism: Oceanians' perpetual hatred for Emmanuel Goldstein, who like Big Brother may not exist; Stalinism, Anti-Semitism and Anglophobia are defined by hatred.

- Transferred nationalism: In mid-sentence an orator changes the enemy of Oceania; the crowd instantly transfers their hatred to the new enemy. Transferred nationalism swiftly redirects emotions from one power unit to another (e.g., Communism, Pacifism, Colour Feeling and Class Feeling).

O'Brien conclusively describes: "The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power."

[edit] Sexual repression

With the Junior Anti-Sex-League, the Party imposes antisexualism upon its members to eliminate the personal sexual attachments that diminish political loyalty. Julia describes Party fanaticism as "sex gone sour"; except during the love affair with Julia, Winston suffers recurring ankle inflammation, an Oedipal allusion to sexual repression.[citation needed] In Part III, O'Brien tells Winston that neurologists are working to extinguish the orgasm; the mental energy required for prolonged worship requires authoritarian suppression of the libido, a vital instinct.

[edit] Futurology

In the book, Inner Party member O'Brien describes the Party's vision of future:

There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.—Part III, Chapter III, Nineteen Eighty-Four

This contrasts the essay "England Your England" (1941) with the essay "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius" (1941):

The intellectuals who hope to see it Russianised or Germanised will be disappointed. The gentleness, the hypocrisy, the thoughtlessness, the reverence for law and the hatred of uniforms will remain, along with the suet puddings and the misty skies. It needs some very great disaster, such as prolonged subjugation by a foreign enemy, to destroy a national culture. The Stock Exchange will be pulled down, the horse plough will give way to the tractor, the country houses will be turned into children's holiday camps, the Eton and Harrow match will be forgotten, but England will still be England, an everlasting animal stretching into the future and the past, and, like all living things, having the power to change out of recognition and yet remain the same.

The geopolitical climate of Nineteen Eighty-Four resembles the précis of James Burnham's ideas in the essay "James Burnham and the Managerial Revolution" [30] (1946):

These people will eliminate the old capitalist class, crush the working class, and so organize society that all power and economic privilege remain in their own hands. Private property rights will be abolished, but common ownership will not be established. The new 'managerial' societies will not consist of a patchwork of small, independent states, but of great super-states grouped round the main industrial centres in Europe, Asia, and America. These super-states will fight among themselves for possession of the remaining uncaptured portions of the earth, but will probably be unable to conquer one another completely. Internally, each society will be hierarchical, with an aristocracy of talent at the top and a mass of semi-slaves at the bottom.

[edit] Censorship

A major theme of Nineteen Eighty-Four is censorship, which is displayed especially in the Ministry of Truth, where photographs are doctored and public archives rewritten to rid them of "unpersons". In the telescreens, figures for all types of production are grossly exaggerated (or simply invented) to indicate an ever-growing economy, when in reality there is stagnation, if not loss.

An example of this is when Winston is charged with the task of eliminating reference to an unperson in a newspaper article. He proceeds to write an article about Comrade Ogilvy, a fictional party member, who displayed great heroism by leaping into the sea from a helicopter so that the dispatches he was carrying would not fall into enemy hands.

[edit] The Newspeak appendix

"The Principles of Newspeak" is an academic essay appended to the novel. It describes the development of Newspeak, the Party's minimalist artificial language meant to ideologically align thought and action with the principles of Ingsoc by making "all other modes of thought impossible". (See Sapir–Whorf hypothesis.) [31] Note also the possible influence of the German book LTI - Lingua Tertii Imperii, published in 1947, which details how the Nazis controlled society by controlling the language.

Whether or not the Newspeak appendix implies a hopeful end to 1984 remains a critical debate, as it is in Standard English and refers to Newspeak, Ingsoc, the Party, et cetera, in the past tense (i.e., "Relative to our own, the Newspeak vocabulary was tiny, and new ways of reducing it were constantly being devised", p. 422); in this vein, some critics (Atwood,[32] Benstead,[33] Pynchon[34]) claim that, for the essay's author, Newspeak and the totalitarian government are past. The counter view is that since the novel has no frame story, Orwell wrote the essay in the same past tense as the novel, with "our" denoting his and the reader's contemporaneous reality.

[edit] Influences

During the Second World War (1939–1945) George Orwell repeatedly said that British democracy, as it existed before 1939 would not survive the war, the question being 'Would it end via Fascist coup d'état (from above) or via Socialist revolution (from below)?' Later in the war he admitted that events proved him wrong: "What really matters is that I fell into the trap of assuming that 'the war and the revolution are inseparable' ".[35] Thematically Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Animal Farm (1945) share the betrayed revolution; the person's subordination to the collective; rigorously enforced class distinctions (Inner Party, Outer Party, Proles); the cult of personality; concentration camps; Thought Police; compulsory regimented daily exercise and youth leagues. Oceania resulted from the U.S.'s annexation of the British Empire to counter the Asian peril to Australia and New Zealand. It is a naval power whose militarism venerates the sailors of the floating fortresses, from which battle is given to recapturing India the "Jewel in the Crown" of the British Empire. Much of Oceanic society is based upon the U.S.S.R. under Josef Stalin—Big Brother; the televised Two Minutes' Hate is ritual demonisation of the enemies of the State, especially Emmanuel Goldstein (viz Leon Trotsky); altered photographs create unpersons deleted from the national historical record.

In the essay "Why I Write" (1946) he explains that the serious works he wrote since the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) were "written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism".[36] Nineteen Eighty-Four is a cautionary tale about revolution betrayed by totalitarian defenders previously proposed in Homage to Catalonia (1938) and Animal Farm (1945), while Coming Up For Air (1939) celebrates the personal and political freedoms lost in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

Biographer Michael Shelden notes Orwell's Edwardian childhood at Henley-on-Thames as the golden country; being bullied at St Cyprian's School as his empathy with victims; his life in the Indian Burma Police—the techniques of violence and censorship in the BBC—capricious authority.[37] Other influences include Darkness at Noon (1940) and The Yogi and the Commissar (1945) by Arthur Koestler; The Iron Heel (1908) by Jack London; 1920: Dips into the Near Future[38] by John A. Hobson; Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley; We (1921) by Yevgeny Zamyatin which he reviewed in 1946;[39] and The Managerial Revolution (1940) by James Burnham predicting perpetual war among three totalitarian superstates. He told Jacintha Buddicom that he would write a novel stylistically like A Modern Utopia (1905) by H. G. Wells.

Extrapolating from the Second World War, the novel's pastiche parallels the politics and rhetoric at war's end—the changed alliances at the "Cold War's" (1945–91) beginning; the Ministry of Truth derives from the BBC's overseas service, controlled by the Ministry of Information; Room 101 derives from a conference room at BBC Broadcasting House;[40] the Senate House of the University of London, containing the Ministry of Information is the architectural inspiration for the Minitrue; the post-war decrepitude derives from the socio-political life of the UK and the USA, i.e. the impoverished Britain of 1948 losing its Empire despite newspaper-reported imperial triumph; and war ally but peace-time foe, Soviet Russia became Eurasia.

The term "English Socialism" has precedents in his wartime writings; in the essay "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius" (1941), he said that "the war and the revolution are inseparable . . . the fact that we are at war has turned Socialism from a textbook word into a realizable policy"—because Britain's superannuated social class system hindered the war effort and only a socialist economy would defeat Hitler. Given the middle class's grasping this, they too would abide socialist revolution and that only reactionary Britons would oppose it, thus limiting the force revolutionaries would need to take power. An English Socialism would come about which ". . . will never lose touch with the tradition of compromise and the belief in a law that is above the State. It will shoot traitors, but it will give them a solemn trial beforehand and occasionally it will acquit them. It will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but it will interfere very little with the spoken and written word".

In 1940 Orwell regarded English Socialism as desirable, hence his activities in achieving it. In the world of 1984 "English Socialism"—contracted to "Ingsoc" in Newspeak—is a totalitarian ideology unlike the English revolution he foresaw. Comparison of the wartime essay "The Lion and the Unicorn" and the post-war novel Nineteen Eighty-Four shows that he perceived a Big Brother régime as a perversion of socialist ideals and of his cherished "English Socialism"; thus Oceania is a corruption of the British Empire he believed would evolve into a "federation of Socialist states... like a looser and freer version of the Union of Soviet Republics".

[edit] Cultural impact

The effect of Nineteen Eighty-Four on the English language is extensive; the concepts of Big Brother, Room 101, the Thought Police, unperson, memory hole (oblivion), doublethink (simultaneously holding and believing contradictory beliefs) and Newspeak (ideological language) have become common phrases for denoting totalitarian authority. Doublespeak is an elaboration of doublethink, while the adjective "Orwellian" denotes "characteristic and reminiscent of George Orwell's writings" especially Nineteen Eighty-Four. This originated the suffixes "–speak" and "–think", i.e. "groupthink" and "mediaspeak", for thoughtless conformity. Orwell is perpetually associated with the year 1984 and the asteroid 11020 Orwell was discovered by Antonín Mrkos in July 1984.

References to the themes, concepts and plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four have appeared frequently in other works, especially in popular music and video entertainment.

[edit] Adaptations and derived works

|

|

[edit] See also

- CCTV

- Censorship under fascist regimes

- Cult of personality

- Dear Leader

- Dystopia

- Language and thought

- Mass surveillance

- Memory hole

- New World Order

- Stalinism

- Totalitarianism

[edit] Notes

- ^ Bowker, Chapter 18. "thesis": p. 368-369.

- ^ Bowker, p. 383, 399.

- ^ Charles' George Orwell Links

- ^ John Rodden. The Politics of Literary Reputation: The Making and Claiming of "St. George" Orwell

- ^ CEJL, iv, no. 125

- ^ Crick, Bernard. Introduction to Nineteen Eighty-Four(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984)

- ^ Goodman, David (31 December 2001). "Orwell's 1984: the future is here: George Orwell believed the stark totalitarian society he described in 1984 actually would arrive by the year 2000, thanks to the slow, sinister influence of socialism". BNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/skaqoz. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Why did George Orwell call his novel "Nineteen Eighty-Four?" , by David Alan Green

- ^ Nineteen Eighty-four, ISBN 978-0-141-18776-1 p.xxvii (Penguin)

- ^ Marcus, Laura; Peter Nicholls (2005). The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82077-4. p. 226: "Brave New World [is] traditionally bracketed with Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four as a dystopia..."

- ^ "Full List — All Time 100 Novels". Time Inc.. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/irdcsz. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Hirtle, Peter B.. "Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States". http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm. Retrieved 25 March 2010. As a work published 1923–63 with renewed notice and copyright, it remains protected for 95 years from its publication date

- ^ Canadian protection comprises the author's life and 50 years from the end of the calendar year of death

- ^ Russian law stipulates likewise

- ^ "Copyright Act, 1978 (as amended)". CIPRO. http://www.cipro.co.za/legislation%20forms/Copyright/Copyright%20Act.pdf. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Australian law stipulates life plus 70 years, since 2005. The law was not retroactive, excluding from protection works published in the lifetime of an author who died in 1956 or earlier

- ^ Pogue, David (17 July 2009). "Some E-Books Are More Equal Than Others". NYTimes.com (The New York Times Company). Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/y6m5tp. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Stone, Brad (July 18, 2009). "Amazon Erases Orwell Books From Kindle". The New York Times: pp. B1. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/18/technology/companies/18amazon.html?_r=1.

- ^ Fried, Ina (17 July 2009). "Amazon says it won't repeat Kindle book recall". CNET.com (CBS Interactive). Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/ne4g5x. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it". "Why I Write" (1946) in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 1 - An Age Like This 1920–1940 p.23 (Penguin)

- ^ The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 4 - In Front of Your Nose 1945–1950 p.546 (Penguin)

- ^ Part I, Ch. 1.

- ^ Part I, Ch. 3.

- ^ "striking thirteen" (1:00 pm). In 1984, the 24-hour clock is modern, the 12-hour clock is old-fashioned, Part I, Ch. 8.

- ^ "Under the Spreading Chestnut Tree". eNotes.com. April 2008. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/ysxudu. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ a b Part II, Ch. 9.

- ^ Part III, Ch. 6.

- ^ Reed, Kit (1985). "Barron's Booknotes-1984 by George Orwell". Barron's Educational Series. http://www.pinkmonkey.com/booknotes/barrons/198423.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "George Orwell: "Notes on Nationalism"". Resort.com. May 1945. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. http://backupurl.com/el6c92. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ George Orwell - James Burnham and the Managerial Revolution - Essay

- ^ "Ethnolinguistics". Mnsu.edu. http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/cultural/language/whorf.html. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ Margaret Atwood: "Orwell and me". The Guardian 16 June 2003

- ^ Benstead, James (26 June 2005). "Hope Begins in the Dark: Re-reading Nineteen Eighty-Four".

- ^ Thomas Pynchon: Foreword to the Centennial Edition to Nineteen eighty-four, pp. vii–xxvi. New York: Plume, 2003. In shortened form published also as The Road to 1984 in The Guardian (Analysis)

- ^ "London Letter to Partisan Review, December 1944, quoted from vol. 3 of the Penguin edition of the Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters.

- ^ George Orwell: Why I Write

- ^ Shelden, Michael (1991). Orwell—The Authorized Biography. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0060921617. ; pp 430-434

- ^ John A. Hobson, 1920: Dips into the Near Future

- ^ George Orwell, "Review", Tribune, 4 January 1946.